In Defense Of Divorce

Rethinking the end of a marriage as a possible part of its purpose.

[Murder Me for Nickels, Arthur Bowen Davies (1960)]

The Case

What do you think about a marriage contract that renews every few years?

In law school, we discussed the possibility of couples having the option to consciously renew or exit their legal union if the original terms that led them to marry in the first place no longer held true over time. Unromantic? Maybe. (Don’t let Mike Ross and Rachel Zane fool you—there’s nothing sexy or romantic about practicing law.) But considering that for around 40% of people in the U.S, “forever” doesn’t mean much (it means even less for second and third marriages), it’s worth rethinking what we’re really promising when we say, “‘till death do us part.”

Divorce is deeply sensationalized in our society, and few portrayals have landed as hard as Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story. The film captures the emotional chaos many adults and their children experience during a separation. One Redditor wrote, “Its depiction of divorce is messy, ugly, and as real as it gets. As an only child with divorced parents, this film had scenes that were, honest to god, handpicked from my early childhood.”

Driver and Johansson’s raw performances hit a nerve. Even people who’ve never been married admitted the film made them cry and wary of the idea altogether. It’s a haunting portrayal of what happens when love runs up against unmet needs, deaf ears, and a bulldog lawyer.

I’d bet anyone reading this knows at least one couple that’s had an ugly divorce.

Media and entertainment’s portrayal of divorce as tragic, complex, and devastating only reinforces the idea: Why even try?

And yet, I’d also bet anyone reading this knows at least one person who’s had an amicable divorce. Those people are like unicorns. Are they real? Are they faking it? Fooling themselves?

We know our thoughts and beliefs shape our emotions and behaviors. So what can we expect when divorce is dramatized, weaponized, and pathologized—especially for women? Can we change the way we view divorce, not as a failure of marriage, but as a possible feature of it?

A Brief History of Marriage, From Sumerians to Raya

In the documentary series The Way of the Dream, Marie-Louise von Franz is interviewed by Fraser Boa, and they discuss the historical evolution of romantic love and its impact on marriage.

You see, marrying for love is a relatively new concept. Gold diggers get a bad reputation, but strategy, alliances, inheritance, and power were the historical foundation of marriage.

Franz traces the earliest stirrings of romantic love to the medieval French courts of love, where knights performed noble acts for the women they idolized (often not their wives). This was a radical psychological shift in human history.

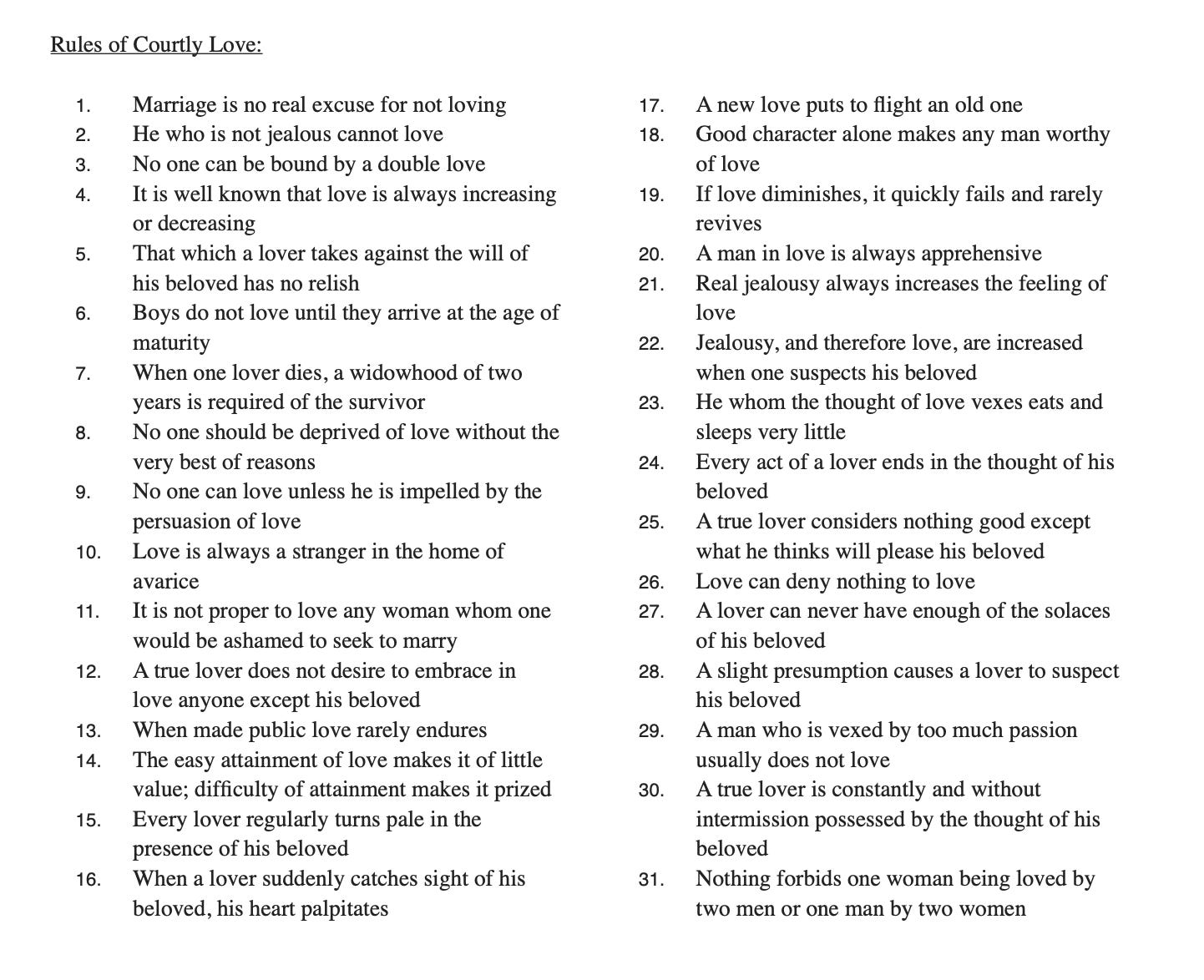

I leave you the rules of courtly love, in case you need some medieval inspiration to woo your boo:

In prehistoric times, tribal pair bonds were formed for survival, reproduction, and protection. These unions were fluid and community-based, rather than exclusive or permanent.

(~2350 BCE): The first marriage contracts appeared with the Sumerians, where labor and inheritance drove people to unite.

(~800 BCE – 400 CE): The Ancient Greeks and Romans were romantics, but marriage was a civic duty that secured social status and political power and rarely involved talk of love.

(~500–1500 CE): The Church elevated marriage to a sacred sacrament in the Middle Ages, though most unions still served the purpose of family alliances. Ironically, it was around this time that the French courts popularized declarations of love and sacrifice—something the Church opposed and suppressed.

It wasn’t until the 19th century, with the rise of Romantic Idealism and Victorian sentimentality, that love began to take center stage in human relationships.

Fast forward to today, and people are trying to find their “soulmate” on Raya.

Love Changed the Game

Marie-Louise von Franz argued it would likely take many decades of trial and error and thus, divorce, before humanity fully understands what it actually takes to live and love only one person for a lifetime. That’s because monogamous marriage initiated for and by love, proposes a special psychological container: a true mirror for the self, a space to examine all the things we project onto another.

Many people, quite obviously, can’t handle that task, because it’s not an easy one. We all have varying levels of self-awareness. Choosing someone to share your life is serious, but not for the reasons the Catholic Church might insist. It’s serious because it asks you to face your own angels and demons in close quarters. To sleep beside someone after giving them your worst and then waking up the next morning to share a coffee. That’s a wildly intimate proposition. It demands emotional endurance, humility, and a willingness to keep showing up.

And still, many take that choice too lightly, sometimes before their frontal lobe is even fully developed. People also keep marrying for reasons outside of love (even if they won’t admit it): money, status, biology, loneliness, horniness. And who are we to judge?

What happens to a relationship once the projections are gone? Franz says that in that moment, the real relationship can begin. Or maybe, you realize there’s nothing left. And is that so terrible? Conditions change. People evolve.

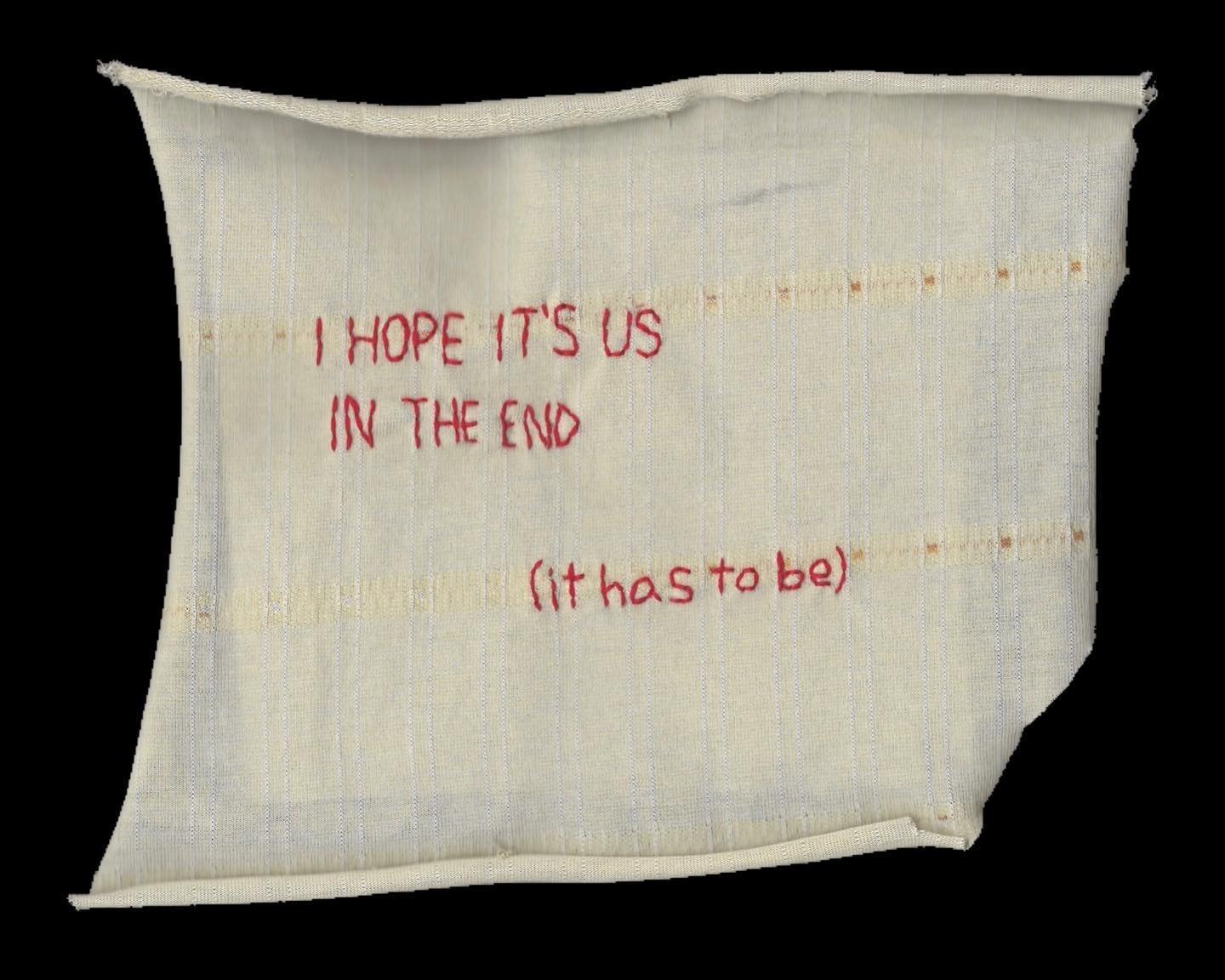

At my own wedding, I gave a speech that raised a few eyebrows in the family. I said I didn’t know if my husband and I were forever—but we were for now, and that was all the certainty we needed, because this moment is all we have.

That mutual awareness gave us the freedom to love each other more honestly and presently. We actually became better friends and partners, precisely because we acknowledged the delicate, possibly fleeting nature of our relationship.

Curiously, when you take the pressure of “forever” off a relationship, suddenly, you don’t really want it to end.

“Liberation of the heart would mean to become slowly capable of feeling and sensing the uniqueness of the other’s personality, and to love that uniqueness. And that doesn’t mean the Christian all-pardoning, sweetie-pie, strawberry sauce love, of loving and pardoning everything. On the contrary, it’s a great precision of feeling. Real love makes the other person whole, it makes the other person more him or herself, and that has nothing to do with sentimentality, or being sweet or polite.”

—Marie-Louise von Franz

Could Divorce Be a Rite of Passage?

And so, if we accept that marrying for love is still new for our species, is it any wonder we’re not that good at it yet?

Love changed the game. Unions are now about growth, intimacy, and healing. The stakes are higher, and the roles we play more complex.

So if we separate, does it have to mean we’ve failed?

We don’t shame people for outgrowing jobs or cities, it’s all growth just the same.

Relationships can offer that type of personal evolution too. So why the tragedy?

What would happen if we saw divorce as a necessary part of the trial-and-error evolution of romantic partnership? If we treated it as a step in human development, could we reduce stigma, remove shame, and make the process more humane?

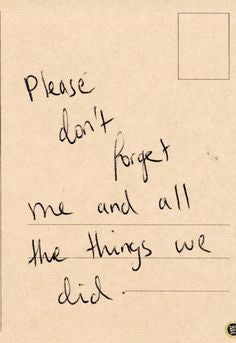

Reframing divorce isn’t a small task. Love lost will always be sad, especially when children, homes and shared dreams are involved. But honoring that pain without pathologizing the ending could be what makes the perfect space for healing.

Could divorce be a rite of passage—or even a success story?

Not because it ended, but because it gave each person a chance to grow—even if that meant growing apart. You get the credit, because you tried, and that’s all any of us can do.

If the goal isn’t to “make it work” at all costs, but to become whole as individuals, together or apart, falling in love and getting married becomes a revolutionary act.

And in it, we can choose to let some people go with grace.

[Man and Wife, Egon Schiele (1917)]