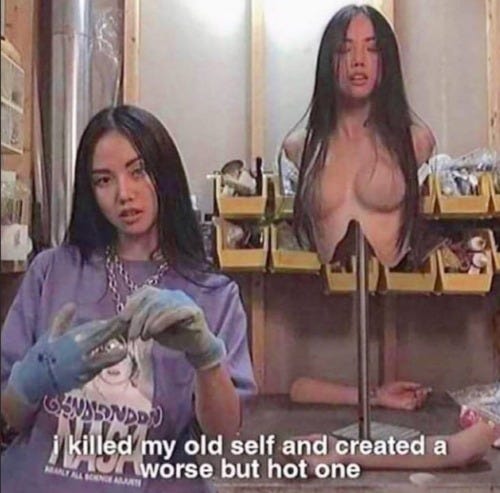

In a World Where Everyone Looks Good, Will It Pay to Be Ugly?

If I were the head of a fashion department, I’d start dressing the Quasimodos in haute couture.

I’m thirty-two years old and I’ve never had cosmetic procedures done. No Botox, filler, or surgery.

Some years ago, gathered around a dining table, I boldly declared to some family members that I didn’t think I’d ever get any work done. One of them audibly scoffed and, rolling their eyes, told me: “Please! With how pretentious you are? Be real.”

Ok, but tell me how you really feel.

I remember playing dress-up in my mom’s closet as little as six years old. Layering on faux pearls, pulling on her leather boots and silk gowns while stuffing socks under my shirt for breasts. I loved the glamour. Va-va-voom! There was a ritual there that I really connected with. Little did I know the innocence of said ritual would be subverted with the passing of time.

I’m Aging

I’m seeing lines on my forehead. My teeth are losing enamel. You could fit a couple of pencils underneath my breasts.

I went to modeling school as a kid, my only real passion besides rollerblades and Barbies. In our first makeup class, we had to do a brown smoky eye. The whole class voted I did the best, which made me beam with pride. I knew I was good, I had it.

Self-assurance doesn’t seem like a quality a child would have, but it is. Children have an ease about them. It isn’t until they start to receive titles and filters that their innate sense of belonging becomes ideologically laden.

I had a strong brush against this phenomenon in my teens. Low self-esteem didn’t begin to cover it, because I had no concept of self and therefore there was no esteem to be had.

It was a long journey for me to befriend myself, but I’m starting to tell the world who I am instead of the other way around (as I confidently did as a kid).

So now, every time I think about getting work done, tweaking my image in some way, the alarm bells start ringing. I wonder if I’m covertly telling myself I’m not enough, a subconscious admission that after all this internal work I’ve done, I still can’t stand the reflection in the mirror. Because if I were really at peace with myself, wouldn’t I just… leave it alone?

Then another voice in my head says: Get over yourself. It’s not that deep.

It Starts Young

Indoctrination starts early for women. Shay Mitchell has recently come under fire for launching a skincare line aimed at children called Rini, and it’s not the only one of its kind. All my niece insisted on for her eighth birthday back in July were products from brands like Bubble or Evereden.

Arguments in favor of this rest on the notion that children have always loved to play pretend, and that everyone wants to “do what mommy does.” Speaking from my childhood interests, this rings true.

They go on to say that it’s teaching children to look after themselves, that it’s an act of love and self-care: a ritual.

I know for a fact there are two ways girls, and later on women, stand in front of a mirror:

One is to pretend we’re in a dress-up montage from a movie. We might dance, stick out our stomachs to imagine what we’ll look like pregnant, or make a funny face.

The other way we stand in front of a mirror is to look, to really take a look. Pick ourselves apart, grab the rolls, brutalize our acne, cry because we hate the reflection staring back at us.

One of those things is expressive and the other is oppressive. Selling skincare to children under the guise of self-care screams the latter.

Judgment of Women’s Choices vs. Critique of Beauty Standards: A False Dichotomy

A woman should be free to choose for herself: appearance, labor, reproduction. Agency is king. And where cosmetic interventions are concerned, as long as you’re making a choice that improves your life and reduces (perceived) suffering, then it’s protected by feminist rhetoric as legitimate.

Many women outright reject the arguments that aging naturally means anything, because it reinforces shame for women who do decide to get anything done and turns the issue into a moral one. Freely chosen, non-coerced decisions taken by women are feminist decisions, period. And don’t you dare say the contrary.

Or… is this lazy and evasive thinking?

“Will Isn’t Free, but Freedom Is Free”: Ancient Eastern Philosophy to the Rescue

If we accept this wisdom, we might come to the conclusion that wanting Botox isn’t a moral failure. Acting on or resisting the desire to partake isn’t empowering or virtuous either way.

But there must be a recognition: it’s not a free choice.

Our will, which is informed by our desires and fears, our upbringing, social imprinting, etc., will never be free. The freedom only exists in observing the arrival of the desires and the decisions we make to witness them without necessarily obeying them.

“I’m 65 and I have the unshakable urge to look like I’m 35.” Interesting… Why is that?

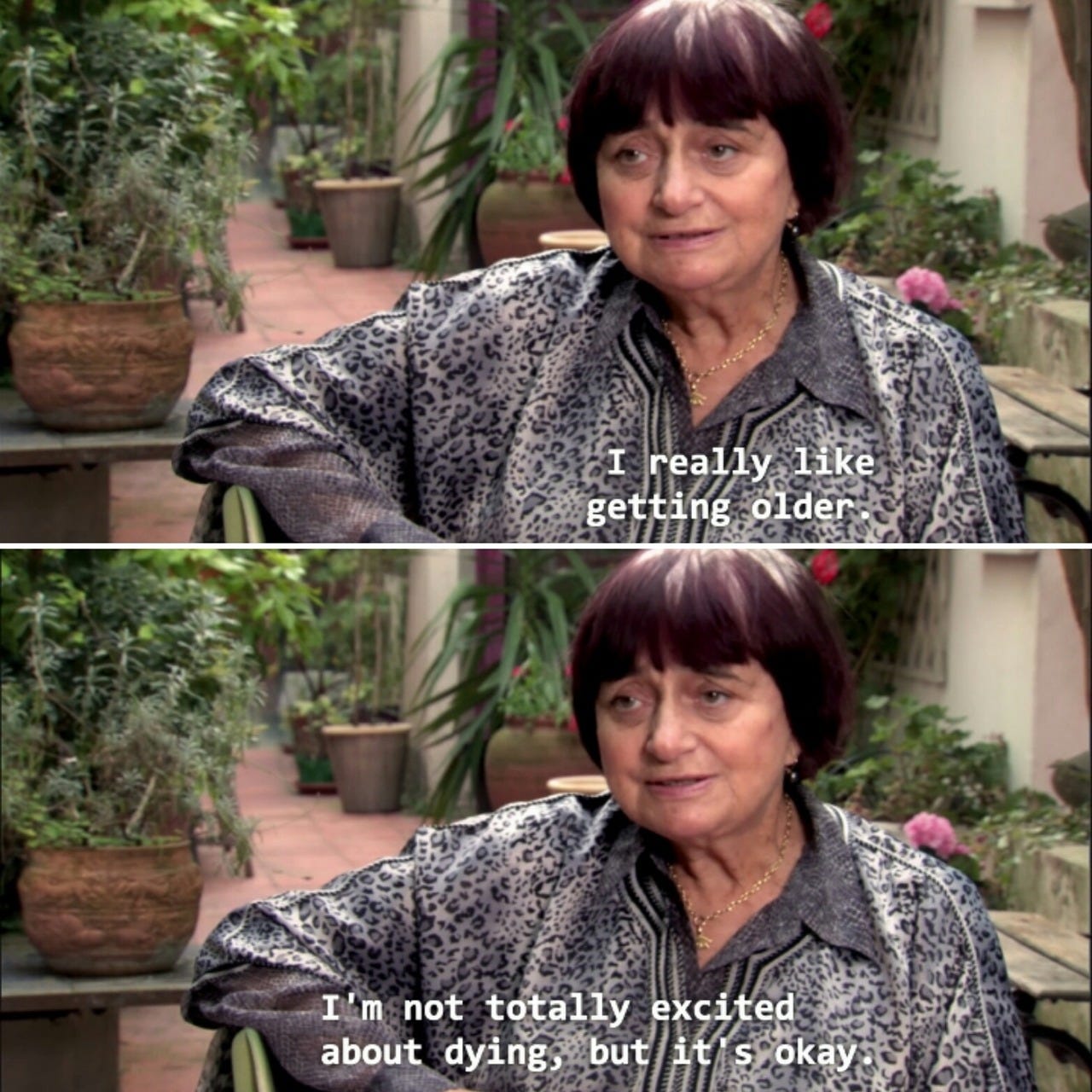

We have to acknowledge the obvious: interventions of the face and body are a form of resistance to death, an attempt to grasp at permanence, denying the very nature of our existence.

Telling ourselves we chose this is not proof of our freedom, and our desires are not a stable foundation for feminist ethics. To intervene ourselves may cause temporary relief, a sense of belonging, a mirage of respect and restoration of balance. And what does this temporary relief create? The baseline of “normal” is unnaturally altered.

How Were Cosmetic Enhancements Sold as Self-Care?

“It’s her choice, none of our business, not important, not that deep”: the most successful marketing tactic in the history of advertising (and the gateway to a modern lobotomy).

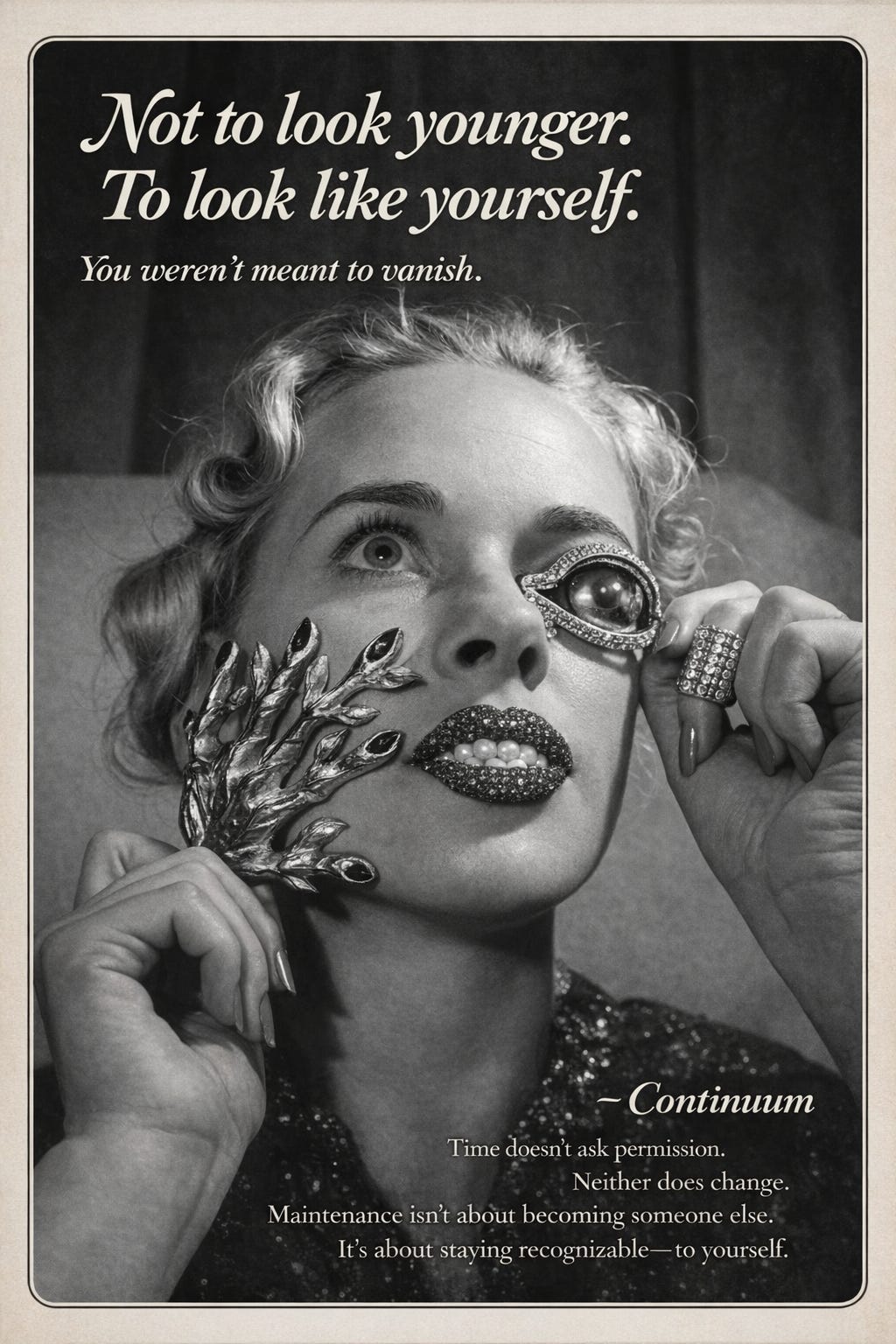

Don Draper would be toasting with bourbon to the genius proposition: selling cosmetic procedures as beauty maintenance and not intervention, so women are compelled to do it forever. Remaining unarmed against time and gravity is framed the same way as not brushing your teeth: decay.

Elevate cosmetic maintenance to the status of health so you can justify the loop, the routine, and the participation as an act of self-care. The ad headline writes itself: “Inject it! Not to look younger, but to remain yourself.”

And of course, get them while they’re young. Why start making money from them at 16 years old when you could start at 6? They had been leaving ten years of profits untapped. How silly! Get them young so you can get them forever.

Therein lies the issue with skincare for children.

Adornment, rituals, and rites of passage are important, symbolic, and necessary. True expression can come from exploring what womanhood is with your friends, mom, grandmother. Gossiping, a bit of rouge, and playing pretend are all anthropological, important forms of expression.

But this is not the same as a system that thrives on keeping us distracted, focused on whether you need veneers or one milliliter more of lip filler. Any parallel drawn by a person trying to sell your child a face mask is an insult to your intelligence.

Of course, this is all further complicated by the fact that nowadays we don’t need printed ads to convince us, we have something far more effective: walking, talking, breathing advertisements. It becomes so much harder to argue with these “choices” when they’re being advertised and promoted by a woman on Instagram Reels.

Selling products and cosmetic interventions as preserving what is already yours also soothes the moral panic and makes the whole thing sound like your idea, an idea rooted in self-love. Paired with unquestioning participants, the status quo shifts and so women who begin to ask questions can be easily dismissed as anal, overthinking, and nosy. Silence is the expectation because it normalizes things over time.

Enter the great divide of 2025: Emma Stone’s facelift at 36. Ask any woman and you’ll get only two answers.

Aging in Media

I was watching Your Friends & Neighbors with my husband and we both commented on how refreshing it was to see Amanda Peet and Jon Hamm looking their age. There’s something magnetic about people who embrace life’s inevitable passage of time, especially when they work in such unforgiving industries. It’s a quiet but powerful signal: I look good no matter what you tell me.

Otherwise, everyone seems to be getting hotter and younger. So I wonder what is that doing to our brains?

Living in the true peak of the nip and tuck, Kylie Jenner just this year shared her exact breast augmentation recipe so we can all get the same silicone cocktail.

What will this do to storytelling in media? Do we feel warmth and connection to characters if they look perpetually youthful and glossy?

If actors have to get mini facelifts in their thirties to keep working, even if it breaks the illusion of the art, what will become of art? Should films reflect our cultural zeitgeist or resist it?

I have no satisfying answers to any of these questions, but I think it’s important to ask them anyway.

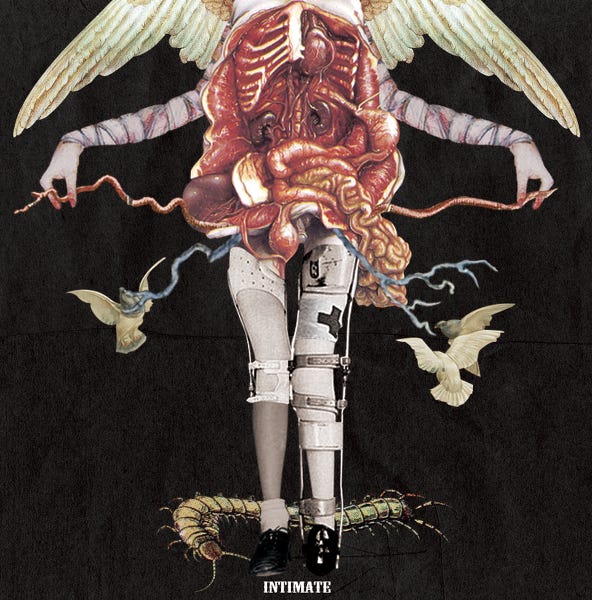

The Substance gruesomely portrays the dangers of excess, the addiction to a look of imagined perfection that can end in the permanent elimination of our likeness. Is it still feminist to fiddle with ourselves to the point of disfigurement? We’re supposed to say yes, and yet for many of us we feel the answer boiling in our blood: no.

There’s a nefarious insult to the self, an erasure. It’s like we’re skipping an important lesson in the name of acceptance of choices: overcoming the demons that drive us to pick ourselves apart in the mirror in the first place.

But not being able to dissect and discuss these topics without backlash isn’t feminist either. All I know is that for myself and young girls, I only wish for more playful mirror sessions and fewer oppressive ones, which the current climate doesn’t reflect.

There’s also an interesting question that comes up: In a world where everyone looks good, can it pay to look “bad”?

A Real Face: An Ancient Artifact

This is where the questions stop lining up neatly and start multiplying instead.

Once we reach the ceiling where we all look incredible but there is no way back, no way to reclaim naturalness, can we reasonably expect to see things get better or just weirder?

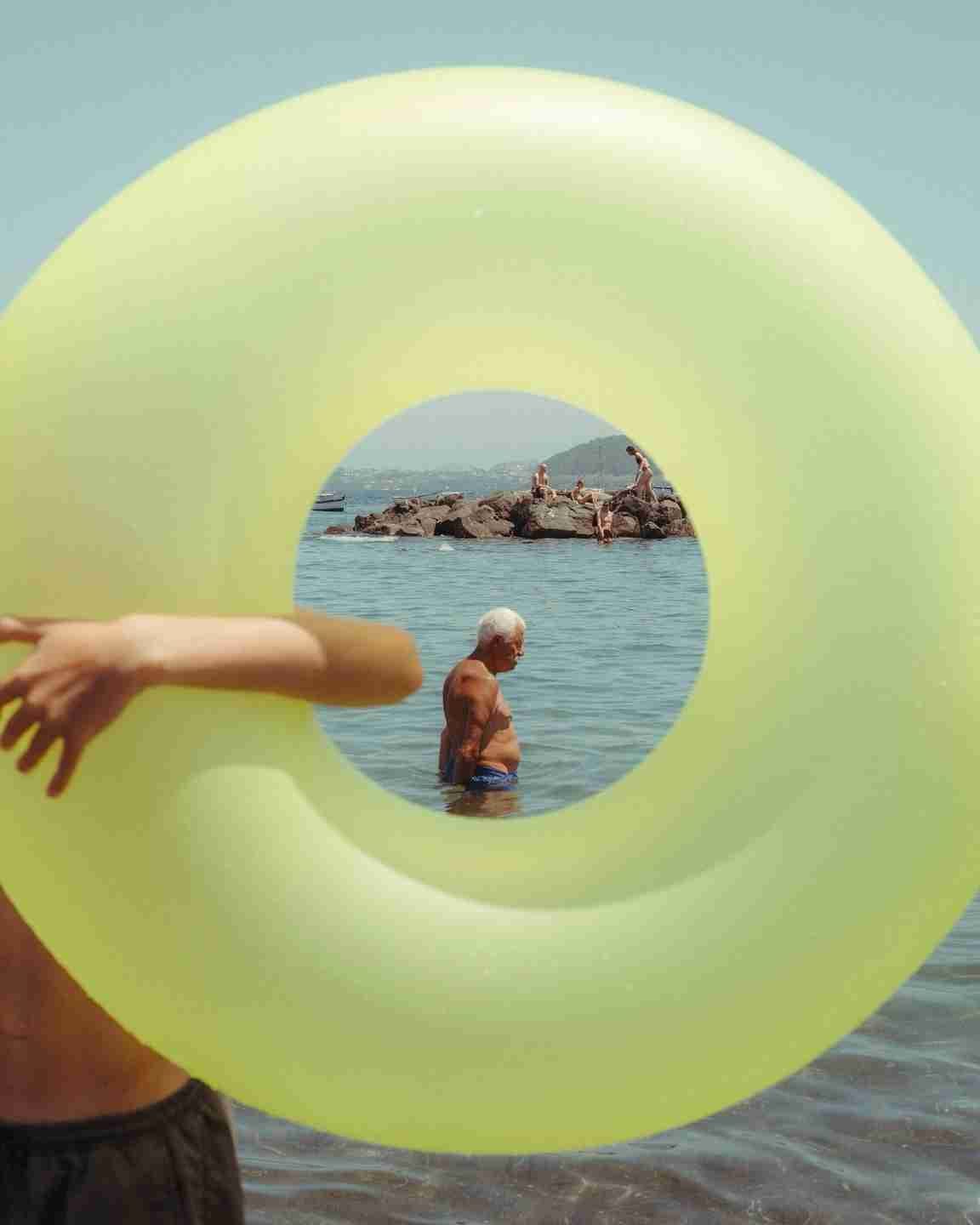

Maybe real faces will become rare treasures, like vintage furniture from a flea market.

Or maybe we’re on the cusp of reclaiming the grotesque and the next big thing will be the flawed, downtrodden, and funky-looking. If I were the head of a fashion department, I’d start dressing the Quasimodos in haute couture just for kicks.

Or perhaps all of this is moot. The birth of artificial intelligence has ushered in a new era for us all. We can sell our faces and voices and remain forever young in algorithm, immortalized by machines that can give us Forever 21 through self-impersonation. The fountain of youth wasn’t water after all, but digital bytes.

At that moment, we might be free to look as crooked, crusty, and creased as we’d like IRL. Or more likely, we’ll keep looking for new ways to stand out.

I don’t think we’re far away from a future where facial prosthetics to look like aliens become a thing. With men out there leaving their wives for ChatGPT and getting off on hentai, I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to expect people to want to look like or marry a Mon Calamari. A topic for another moment.

Final Reflections

I’m starving for more images of untampered aging. Not because I have judgments about how other women should age (despite my objections), but because I’d like more references so I can make up my own mind.

I don’t think our obsession with anti-aging is just about vanity. Looking at ourselves, literally and symbolically, gets harder the longer we live. The older we get, the less we can hide from who we really are and ultimately from death.

Will our wrinkles be the burden of proof of reality? Will aging become a symbol of status, reclaimed as symbolic and beautiful, not a process to be corrected but celebrated? Naturalness as proof of authority, continuity, and intelligence.

The furrow in a thinking writer’s eyebrow, the wrinkled arms of an interstate truck driver, the sunspots on a farmer’s face, the hunched back of a crouching laboratory scientist.

In the end, I’m just like anyone else: a lover of trends and a hypocrite.

If I’m anticipating that keeping my real face will be a prized commodity, I’ll cling to my wrinkles as long as I can tell a good story about how it makes me better than you.

(P.S. For the curious: procedures I myself am contemplating = breast reduction & lift, lip hydration, Botox around the eyes. Only time will tell if I’m gangster enough to resist.)

Xoxo

Virago